A one-act play for children in whose families a person is living with Alzheimer’s disease or a related form of dementia.

By JC Sulzenko

THE GUIDE DATES FROM 2008, UPDATED 2025

Inside this guide

- Questions to kick-off a discussion

- The script

- FAQs

- Activities

- Sources of information and reading

Text copyright (the play and guide) © JC Sulzenko, 2008

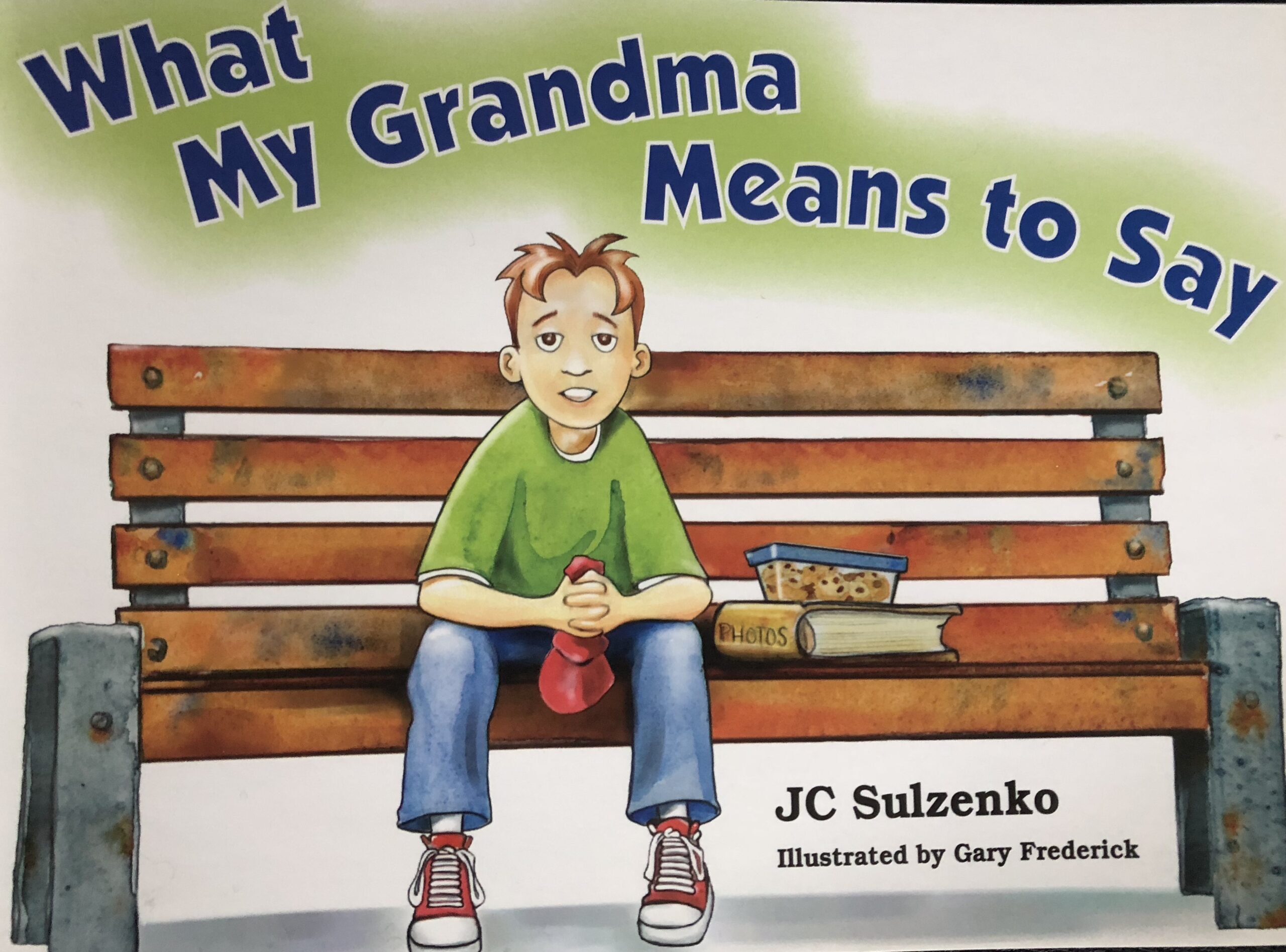

Cover illustration © Gary Frederick, 2011

All rights reserved. Except for a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review, or a school/academic institution which may ‘perform’ the play as a not-for-profit organization (subject to a licensing agreement from JC Sulzenko), no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, JC Sulzenko.

E-mail: infosulzenko@gmail.com Website: www.jcsulzenko.com

First published in Canada in 2009; revised as a digital version in 2012

ISBN 978-0-9685094-5-6

Designed by: Mag Carson, Art Director, General Store Publishing House

First printing in Canada by: Laser Zone Print and Copy, Ottawa

Second printing in Canada by: New Printing Inc.

For information on the play and access to the PDF version of the Discussion Guide, go to www.jcsulzenko.com

For information on What My Grandma Means to Say, the storybook, go to www.jcsulzenko.com

The Play and Discussion Guide for

What my grandma means to say

(The Blue Shawl)

A one-act play for children in whose families a person is living with Alzheimer’s disease or a related form of dementia.

By JC Sulzenko

This ten-minute, one-act play gives elementary school-aged children (Grades 4, 5 & 6) and their families the chance to learn in a gentle way about how Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias can affect a person and what they can do to support the person living with the illness. The setting, created by a performance or reading of the play, encourages children to ask questions in a safe-feeling environment, moderated by a teacher or community member who uses the questions and answers in this Discussion Guide to explore issues children raise about Alzheimer’s. The Guide has suggested activities to build awareness and understanding of such diseases.

To see a pilot performance of the play as performed by a troop of high school students, go to: http://youtu.be/WsaHth8bm0s

The Discussion Guide can also be used in conjunction with reading What My Grandma Means to Say, the storybook adaptation of the play, which creates a similar opportunity for learning about Alzheimer’s.

Inside the Discussion Guide

- Why a play?

- How to use the play

- How to start a discussion after the play: kick-off questions

- Answers to FAQs

- How you can help

- Activities in the classroom or at home

- Sources of further information

- What my grandma means to say: the script of the play

- About the playwright

Why a play

Based on a true story, the play lets children share the experience of a conversation between a grandson and his grandmother who is living with Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s poses multigenerational challenges. Often children in families that face a crisis in the health of loved ones only know part of the story. Having only a little information can prove more frightening to them than if they come to understand what is going on.

Through seeing or hearing the play or reading the storybook based on it, children (and their families) gain an opportunity to raise questions and find out what they want to know in a setting removed from the actual situation with which they must deal. Children need the chance to find their place in what is happening and to build their own understanding and strategies, especially since they often are drawn into the role of caregivers.

How to use the play

The play can be read aloud, with all its stage directions as occurs in a ‘Reader’s Theatre’ approach (where the reader includes the stage directions and descriptions of the setting when reading the play aloud.) The play can be performed in a community setting or at a school. In the classroom, students can be encouraged to take on the roles in the play.

Contact JC Sulzenko at infosulzenko@gmail.com if you mean to stage the play outside of a single classroom reading to learn of any applicable licensing requirements.

Before the play, set the scene for the children (and audience) with the following points as guidelines:

- The play you are about to see/hear looks in on the life of eleven-year-old Jake as he visits his grandmother at a long-term care residence where she lives.

- She is seventy years old and living with Alzheimer’s disease (one of a large group of disorders known as ‘dementias.’)

- Such diseases cause differences in the ways people remember and how they think.

- Alzheimer’s disease is NOT a normal part of growing old. (Young children cannot get Alzheimer’s.)

- This is not Jake’s first such visit with his grandma, but something very different happens this time.

- After the play, there will be time to talk about what happened to Jake and his grandma and to discuss any questions that come to mind.

You may jump to the script of the play.

How to start a discussion after the play: kick-off questions (After the play, use the kick-off questions (below) to help launch the discussion. Usually, one or two questions will prompt children to ask their own or to raise anecdotes from their own experience.)

- How do you think Jake feels after what happened in the garden? (Prompt, as necessary: was he happy?)

- How did the play make you feel?

- How many of you have heard about Alzheimer’s disease before today? Have you heard the names of other illnesses or conditions where people have problems remembering things?

- Why did Jacob become so excited about his Grandma when she talked to him in the garden about the birds?

- Do you think Jacob will continue to visit his Grandma? What makes you think so?

- What did Jacob and his Grandma do together during their visit?

- How would you feel about visiting someone in a place where elderly people live because they need special medical care? (Such places are often called long-term care residences.)

- What kinds of things could you do while visiting someone in a long-term care residence? (See suggested activities later in this Guide.)

Answers to FAQs

What is Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is one of a large group of disorders known as ‘dementias.’ Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and may contribute to 60-70% of the cases.

These diseases cause differences in what people remember and how they think. People with dementia may show signs such as loss of memory, difficulty in making decisions and thinking things through, confusion, and changes in the way they behave. Sometimes it’s difficult to understand what is being said, because the part of the person’s brain that organizes the way people speak may not be working well.

How did the disease get its name?

It was named after a doctor in Germany, Dr. “Alois” Alzheimer, who, over one hundred years ago, described the first patient with the disease. He determined how to find out whether a person who has died had been affected by Alzheimer’s.

How rare is it?

It was estimated that almost 800,000 people in Canada were living with dementia.

Does it happen only in old age?

Most people who have the disease are well over sixty-five years old. Sometimes, though not very often, people in their forties and fifties can get it, too.

In 2024, 8.7% of people in Canada over age 65 have some form of dementia.

Alzheimer’s is NOT a normal part of growing old. Not everyone’s grandfather or grandmother is going to get the disease.

If you are forgetful, do you have Alzheimer’s?

Everyone is forgetful from time to time. That’s normal.

What is the difference between amnesia and Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s is a disease of the brain that affects how a person thinks and remembers. It gets worse over time. Amnesia usually refers to a sudden loss of memory.

How do you get it? Is there a way a younger person can know if they will get the disease?

Children do not get Alzheimer’s. Young people cannot catch Alzheimer’s disease from another person, like the cold or the flu. They cannot catch it by touching or by hugging someone with it.

Scientists don’t know why people get Alzheimer’s, but they are working hard to find a way to stop it from happening.

People with a family history of Alzheimer’s disease do run a greater risk of getting it in later life. This does NOT mean another member of the family will get the disease just because someone in the family has Alzheimer’s.

How do you know if you have it?

There is no single test to tell if a person has Alzheimer’s. To find out, a doctor does physical tests and looks for problems with the person’s memory: how they think, speak, and make decisions, and how these all affect the way the person manages life day to day.

Once you have it, do you have to live with Alzheimer’s disease?

Yes, you do. There are medicines that can help manage and ease the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Over time, people living with Alzheimer’s disease will need assistance with chores, driving and getting dressed. Feeling loved and supported by family and friends, eating healthy foods and exercising regularly can help people live better with this disease and adjust to the changes as they come.

What are the stages of the illness?

There are three stages of Alzheimer’s disease: early, middle and late. Over time, people with Alzheimer’s find it harder and harder to do all the different things that they used to do every day like getting dressed or making a meal. Their memory gets worse, they become more confused, they have difficulty making good decisions, and they have problems speaking and finding the right words. They find it harder to concentrate, and their feelings are often mixed up. For instance, they can become anxious or angry for no reason others around them can understand.

Can you die of the illness?

Yes. The outcome of Alzheimer’s is passing away. A person with Alzheimer’s lives between three to eleven years and can live as many as twenty years from the start of the signs that they have the disease.

Over time, the body shuts down, because the brain, which is the center of all functioning in the body, and which controls walking, talking, breathing, and eating, is shutting down. Often the person dies from another illness, such as pneumonia, as the person’s body has become very weak during the course of Alzheimer’s.

Does a person’s brain change when they have the disease?

Yes, the brain changes in how it works, and it loses size and weight.

Does the disease affect only the inside of the brain or also what the person looks like?

Both. Because the brain is the control centre for the whole body, it controls the way a person uses their body and, therefore, how he or she may appear. So, during the years that a person might live with Alzheimer’s, the disease can affect what a person looks like. For example, with Alzheimer’s, a person can forget how to move.

If you have the disease, can you forget how to talk?

The disease does change the way people communicate with words. Some people lose all their words. That does not mean they cannot understand some or all of what people say to them or some or all of what is going on around them.

Can medicine help if you take it as soon as you know you have the illness? Can it stop the illness? Can you get better?

As of today, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, but there are medicines that help manage and ease the symptoms.

Is there a vaccine?

There is no vaccine and no way to prevent the disease that we know of yet, but researchers around the world are focusing on the disease.

Is there a way to prevent Alzheimer’s?

Not as of yet. Researchers are studying ways to reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Leading a healthy lifestyle and having a healthy diet, along with getting lots of exercise and staying active, can help keep our brains healthy. Protecting your head with a helmet during sports can help protect your brain from injury. In fact, scientists are doing research to learn about any links between brain injury and dementia.

People can exercise their brains at any age by learning something new every day, playing with friends and spending time with their families.

What does it feel like to have Alzheimer’s disease?

People with the disease sometimes may not know where they are or lose words. They may not understand what things are for, which makes them more confused. For example, they might not remember how to use a phone.

As time goes by, people living with Alzheimer’s may not respond to questions or activities in the way a visitor would expect. Talking with them may become one-sided. People with Alzheimer’s may repeat a question over and over again, or look out the window. Being there with them, showing affection and interest in them by sharing stories, drawings and readings with them still matters, though.

Is there any point in visiting someone who has Alzheimer’s, even if they don’t recognize you?

Yes, there is. People with Alzheimer’s disease need to know that you care. When you hold their hand or give them a hug, they will feel your affection.

Can the disease make people angry or upset with their families and friends?

The brain helps a person understand the world around him or her. When Alzheimer’s disease changes the way a person’s brain works, a person living with the disease sometimes may act in unexpected ways for an adult. If a person becomes angry or shouts, it is likely because he or she feels confused and frightened. Loud noises, crowded spaces, feeling lost, or tired can cause a person to act this way. It’s not the fault of the friend or family. It’s not personal, either.

What can children do if something that worries them happens during a visit to a person living with Alzheimer’s disease?

Leave the room where you are visiting. Tell an adult you are worried and ask for help. People with Alzheimer’s usually need quiet time to calm down.

What kinds of things can you do when you visit someone who has the disease?

Short visits usually work best. People with Alzheimer’s often need help to feel happy and secure. Family and friends can show their affection by holding the hand of the person they have come to see. Bringing something to talk about or do together during the visit is a good idea, such as reading out loud, or looking at books, family photos, or magazines.

Having something to do and a place to go can give visitors and the person with Alzheimer’s something positive to focus on while they spend time together. Activities such as looking at a memory box, singing songs and creating art projects can work well. So can going outside in good weather to look at nature.

Visitors also can offer reassurance. For example, when a young girl visits her grandfather, who has dementia but still knows his granddaughter’s name, she tells him stories about their family. He says to her, “You are my memory.”

Do people have to live in a long-term care residence when they have Alzheimer’s disease?

Eventually, people with Alzheimer’s disease usually need the kind of care and support that is provided in long-term care. These residences are designed specifically to help people take their medication and to assist them with everyday tasks such as walking and bathing. Such attention is given by doctors, nurses and support workers trained to provide medical care to people who are living with a condition such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Can music help?

Yes. Music can help stimulate a person’s memory and make that person feel good. Sometimes, people with Alzheimer’s can remember their favourite songs, even when they may have difficulty speaking in sentences. Music can provide a positive experience during visits from family and friends. It’s joyful and fun.

Do service (therapy) dogs help people with Alzheimer’s?

Visiting someone living with Alzheimer’s and bringing along a pet can often be very comforting to someone with the illness. Check with the residence where a family member or friend lives to see if you can be part of a pet therapy program there.

How you can help

Visiting someone who has Alzheimer’s disease

See above.

Because people with Alzheimer’s disease need help to feel happy and secure, short visits usually are best. When family and friends visit someone with Alzheimer’s disease, they can show their affection by holding his or her hand. It’s helpful to bring something to focus on during the visit. For example, something to talk about or do together, such as reading out loud and looking at books or pictures or magazines or signing.

Visitors also can offer reassurance. For example, when a girl visits her grandfather, who has dementia but still knows his granddaughter’s name, she tells him stories about his family. He says, “You are my memory.”

At times, visiting with the family pet, a dog or a cat, can comfort the person if where the person lives is pet-friendly.

What else can families do?

Create a list of suggestions for visitors.

With the family, brainstorm about how you can spend time with the person living with Alzheimer’s disease. Some examples: are going for walks, bird watching, playing card games, listening to music, singing, and eating ice cream.

Remember past events.

People living with Alzheimer’s disease like to remember things from long ago. You can help them remember by sitting with them and looking at old pictures, photo albums, books or magazines.

Memory Box.

You probably have many special memories about spending time with the person who is living with Alzheimer’s disease. Fill a box with five special things that will help you to remember those times when you show the box to the person with Alzheimer’s.

The box can be a shoebox decorated with your drawings or magazine cut-outs. It can be an old fishing tackle box or an old purse.

The possibilities of what goes into the box are as endless as your memories. A coin, a letter or postcard, a piece of jewelry, a medal, a baseball or golf ball, and a movie theatre ticket stub are some examples

Activities for teachers and their students (and their students’ families)

- Life Story Collage. Students can interview a grandparent and/or family members and then create a scrapbook to contain images along with answers to questions such as where the person living with Alzheimer’s was born? Where did he or she grow up? What is his/her favourite ice cream?

- Create your own ‘time capsule’: Like the memory box described earlier, students each can create a ‘time capsule.’ Into whatever container they choose can go examples of what really interests them at that moment in their lives: Objects, photos, games, almost anything, except food or material that can spoil, can be placed in the ‘time capsule.’ Once filled, decorated and closed, such ‘time capsules’ can be put away and kept in a safe place for five to ten years. When the students open their ‘capsules,’ inside will be objects that remind them about what was important to them when they were younger.

- Creative Writing. Ask students to write a story about the life of the person in their family or someone they know well who is living with Alzheimer’s disease. The story can be fiction or non-fiction. What story could they write for and about a grandparent or a family friend, for example?

- More information. Go to these Canadian websites https://www.baycrest.org and https://alzheimer.ca/en.

- Read the play aloud with the class or perform it.

- The play can be read aloud, with all its stage directions as occurs in a ‘Reader’s Theatre’ approach (where the reader includes the stage directions and descriptions of the setting in reading the play aloud,) or performed in a community setting or at a school in a classroom.

- Encourage students to take on the roles of Jake and his grandma, either in front of the whole class or in pairs, with each other. Consider giving students the chance to exchange roles and share, afterward, how their feelings changed when they reversed roles.

- (Here’s another approach: seek a partnership with a high school or college drama class, so that older students perform the play for one or a number of elementary school classes or schools. Watch a pilot performance of the play by high school students at: http://youtu.be/WsaHth8bm0s).

Producing and Directing the Play

Please note: If your organization wishes to put on a production of the play outside of an individual classroom reading, please contact infosulzenko@gmail.com to learn of any applicable licensing requirements.)

Before seeing or hearing the play, set the scene for the audience, with the following points as guidelines:

- The play you are about to see/hear looks in on the life of eleven-year-old Jake as he visits his grandmother at a long-term care residence where she lives.

- She is seventy years old and living with Alzheimer’s disease (one of a large group of disorders known as ‘dementias.’)

- Such diseases cause differences in the ways people remember and how they think.

- Alzheimer’s disease is NOT a normal part of growing old. (Young children cannot get Alzheimer’s.)

- This is not Jake’s first such visit with his grandma, but something very different happens this time.

- After the play, there will be time to talk about what happened between Jake and his grandma and to discuss any questions that come to mind.

Use the kick-off questions and FAQs listed earlier in this Guide to launch and guide a discussion. You can contact your local Alzheimer Society or national Alzheimer society for more information.

- Reviewing the play. After seeing or hearing the play, ask students to write a review or give a talk on how their understanding of such illnesses has changed. Share such comments among the students and with others, even with your local Alzheimer society.

Sources for further information

For more information, you can go to the websites or contact the offices of the Alzheimer Society nearest you, or of your provincial or state Society or national Alzehimer organization. Local public libraries can suggest good books on this subject for every age group. There also are international organizations and annual conferences with Alzheimer’s as their focus.

Note: The script is available as a stand-alone document for printing and distributing.

What my grandma means to say: the script

For Livia Janak

What my grandma means to say

(The Blue Shawl)

Characters [to consider: for ‘fun’ could postage stamp-sized insets of each character’s face from the book’s illustrations appear next to their names on the list?]

Jacob/Jake: an eleven-year-old boy

Grandma: Jake’s seventy-year-old grandmother

A Nurse: the attendant at the desk

Jacob’s Mother: Grandma’s adult daughter

Voices off stage

Locations

A room, a corridor and a garden in a long-term care residence

© JC Sulzenko, 2009

(The scene:

A boy around eleven years old stands in the open doorway of a long-term care residence room, his back to the audience. He’s wearing a baseball cap, jeans and sneakers, and an ordinary tee shirt. To his left, there’s a railing, as one finds along a corridor in a place where people need something to hold onto because walking is difficult for them.

The door to the room is a simple frame without walls so that the audience can see the whole room, with the shape of a single bed and bedside table inside it. A large bulletin board, covered with family photos and pictures of different birds, can also be seen, as though suspended from an invisible wall. Opposite the frame of the door is the frame of a window. It gives onto a brick wall of another building, perhaps across a laneway that’s several stories below.

Inside the room, a small woman, around seventy years old and dressed in a tracksuit, waits in a wheelchair. She sits almost straight in her wheelchair.)

GRANDMA: Hello. You are? …

JACOB: I’m Jacob, Jake. You remember grandma.

GRANDMA: Of course, I do. Of course… You are? You are…

JACOB: Your grandson, grandma. I’m your grandson. Jake. You know THAT, Grandma. You know.

GRANDMA: Of course, I do. Of course. Would you like a…, a…

JACOB: (He looks at the food on the side table.) A raisin? A candy? A cookie? Grandma: would you like a cookie? (He picks up the bag of cookies from the side table and pulls one out of the bag). See, this is a chocolate chip cookie, Grandma. It’s got little bits of chocolate in it. They crunch. Here, have one. (He hands it to her and munches on one himself.)

GRANDMA: Ummmm, good. (Jake nods.) I’ve never had a…, a…

JACOB: A chocolate chip cookie? Maybe you’re right, Grandma. Maybe you never had one just like this. When I came last Saturday, you tried oatmeal chocolate chip cookies. They’re good, too. You liked them a lot.

GRANDMA: I did?

JACOB: Sure. You ate at least three!

GRANDMA: I did?

JACOB: Yup, you did. Would you like to go outside for a walk, Grandma?

GRANDMA: A walk? I’m in a…, in a… (She looks down at her feet.)

JACOB: In your wheelchair. I know, I know. I could push it outside. We could sit where the birdfeeder is. We could count the birds.

GRANDMA: Count the birds…, the birds…

JACOB: Yes, let’s go outside. Here’s your blue shawl, in case it’s chilly. (He picks it up off the bed and hands it to her.) That’s it. (Grandma tries to put her arms through the armholes as if it were a sweater.) No, you don’t need to put your arms through, Grandma. It’s got no sleeves. Here, let me wrap it around you. Just sit a little forward. (Jake drapes the shawl over her shoulders.) Okay. You can lean back now. Isn’t that cozy? Here we go.

(Jake pushes her out of the room, down the corridor, past the frames of open doors that hint at many rooms along the hall. As they walk down the hall, they pass a few men and women holding onto railings or pushing walkers on wheels toward the end of the corridor. Other folks sit in wheelchairs at the doors of their rooms. One man uses two canes. His progress is slow as Jake and Grandma pass by him.)

VOICES OFFSTAGE: Coughing, throat clearing

OTHER RESIDENT OFFSTAGE 1: “Alice?”

OTHER RESIDENT OFFSTAGE 2: “Henry?”

GRANDMA: Where are we… Are we…

JACOB: We’re going outside, Grandma. We’re going outside. To see the birds.

GRANDMA: The birds…, the birds…

(Jake pushes the button to open the door to an enclosed garden. Alcoves hold pots of blood-red geraniums that break up the stiff, high planks of the fence that keep the residents separated from the street and safe, inside the flowered walls. There are a few chairs and tables, perhaps an awning, and other patio furniture. Jake pulls up a chair next to Grandma’s wheelchair.)

JACOB: Here we are. Let’s sit here. That way the sun won’t be in your eyes. I’ll lock the wheels. (Jacob sits down.) And we’re not too close to the birds. We don’t want to scare them away. Are you comfy?

GRANDMA: Scare them? Comfy… Am I…

JACOB: Comfy. That’s a ‘yes,’ I guess, Grandma. Oh, look! A chickadee! (He points to the feeder.)

GRANDMA: Chickadee-dee-dee! Chickadee-dee-dee!

JACOB: Yes! That’s right. You remember those birds, Grandma! You used to take me on the trail in the winter! (Grandma nods at each sentence in his description. She becomes more attentive, involved, animated and understanding at each of his statements.) We’d bring safflower seeds. You’d put them in our hands. The chickadees swooped down, didn’t they? They whirred through the air and landed right in our hands. They weighed nothing. I remember their bright, black eyes and cold, sharp little feet, even if you don’t!

GRANDMA: (She’s smiling and nodding her head.) Chickadee-dee-dee! Chickadee-dee-dee! Look: a cardinal! (Grandma points at the bird.)

JACOB : (Jake sits up straight; stares at his grandma, his face open with surprise.) What did you say, Grandma?

GRANDMA: A cardinal! See, it’s there, in the little cedar.

JACOB: A cardinal? A cedar? (Jake stands up and bends close so that his face is level with his grandma’s.) Grandma: do you know what you just said?

GRANDMA: Yes, dear. I sure do.

JACOB: (Jake shakes his head in disbelief.)You’re right about the cardinal, Grandma. There’s its mate, too. See? (He points. Grandma nods.) And the tree. You knew it was a cedar. That’s awesome. That’s amazing, Grandma! (Jake hugs her. He’s grinning.) Wait till I tell Ma.

GRANDMA: Now, Jake, no need to make such a fuss. You know I know all about birds. Taught you how to look for them. How to listen for their songs. How to feed them. Why are you so surprised?

JACOB: Grandma, it’s just that… that… (Jake takes off his cap and twists it.)

You haven’t been talking much when I’ve been over to visit, Grandma. And sometimes, sometimes you forget things.

GRANDMA: Oh, Jake. It’ll take a long time for me to forget what I know. And a long, long time for you to know half of what’s in my brain. (Grandma chuckles and points to her own head).

JACOB: Maybe I should call Ma. She’ll be so happy to hear about the birds, about the tree.

GRANDMA: Oh no, Jake, dear. Let’s just have a nice time together. Look, a goldfinch near those lilies.

JACOB: A goldfinch! Lilies! (Jake shakes his head in amazement.)

GRANDMA: You sound like a parrot, dear. Now, it’s your turn. See that black bird with the wide tail? Can you tell me what it is?

JACOB: It’s a…It’s a…

GRANDMA: Ah ha! Give up? It’s a grackle. Time to get out that bird book I gave you. Time to refresh your memory! (Grandma points at Jake and chuckles.)

JACOB: My memory? You’re right, Grandma. You’re so right! (Jake hugs her.) Look, Grandma, stay here in the garden. Just for a couple of minutes. I’ve really got to call Ma. I’ll be right back.

GRANDMA: Sure, dear. I like it out here. Don’t rush yourself. I’m not going anywhere in this thing. (She pats the arms of her wheelchair, chuckles and waves him off.)

(Jake pushes the button and runs back into the building, to the central workstation on that floor, where a uniformed nurse works.)

JACOB: I need to use the phone quick, please. Quick!

NURSE: Is anything wrong?

JACOB: (Everything Jake says rushes out of him in a rapid stream.) No, no. It’s just so awesome! It’s my grandma: she usually forgets stuff. Forgets everything. But just now, she knew me and about the birds in the garden. She could name them! I gotta tell my Ma to come right over. I know she won’t believe me. How grandma is cured!

NURSE: Here’s the phone. (The nurse turns the phone around so Jake can use it.) But look, don’t set your hopes too high. Sometimes, people who live here remember some things for a little while and then go back to forgetting again.

JACOB: No way. No way. My grandma’s back! (Jake picks up the phone and ‘dials.’) Hello, Ma? Guess what? You ‘gotta’ come over right now. No, nothing’s wrong. But Grandma remembers stuff…

Yes! She remembers my name! And she knows the names of the cardinals and the chickadees. And the cedar tree. She even remembers the bird book she gave me for my birthday… No, I’m not kidding, Ma. It’s so awesome…

Yes. Okay. I’ll wait with her. We’re in the garden. Hurry, Ma. Hurry!

(Jake hangs up the phone and turns it back to the Nurse.) Thanks a lot!

(The nurse shakes her head as Jake turns around and runs back down the hall.)

JACOB: (Jake bursts into the garden. He’s smiling like a clown.) Grandma, Ma is coming to see the birds with us. She’ll be right over.

GRANDMA: (Grandma smiles.) That’s nice…

JACOB: Look, Grandma, a…? (Jake points to a blue jay at the birdbath.) You know what ‘kinda’ bird that is, Grandma. Tell me! (His smile is triumphant.)

GRANDMA: (Grandma smiles back at him.) It’s a… It’s a…

JACOB: Grandma? (Jake loses his smile as he watches his grandmother work the edges of her shawl and furrow her brow.) Tell me what kind of bird that is. You know the names of all the birds.

GRANDMA: It’s a… It’s a…

JACOB: What kinda bird? Just say it! Grandma, say it! (Jake’s questions escalate into demands. Now he is shouting.) Grandma, tell me!

(Grandma starts to whimper. She shrinks away from him and tries to shelter under her shawl. Jake stands up slowly and walks over to her. He puts his arms around her.)

JACOB: It’s a Blue Jay, grandma. It’s a Blue Jay. See how well you taught me? I knew what bird it was. (He pats her hand.) I’m sorry I shouted, Grandma. I’m really sorry.

That’s better. You’re okay now. (Grandma nods, smiles a little again.) It’s getting late. Let’s go in. Let’s go in.

(Jake turns the wheelchair around, pushes the button and pushes Grandma in her wheelchair through the door into the building. We see his retreating back, shoulders slumped, as he pushes the wheelchair away from the garden’s light toward his mother, who is walking quickly down the corridor toward them, her face to the audience.)

JACOB’S MOTHER: Hi Jake, Hello Mother. How are …

As she sees Jake shake his head in a silent ‘no,’ she stops speaking in mid-sentence. Her smile shrinks to a tight line.

JACOB’S MOTHER: Oh my darlings. My darlings…

Still facing the audience, she leans down to caress her mother’s cheek, then comes around to stand next to Jake. She puts her arm around Jake’s shoulders. Their backs to the audience, they together push the wheelchair further into the heart of the nursing home.)

About JC Sulzenko

JC Sulzenko, Ontario poet, author and playwright, is known for writing workshops and projects she leads with young and emerging writers. Her play for children, What my grandma means to say, premiered at the Ottawa International Writers Fall Festival in 2009.

The play has been performed and presented to many schools and in community settings since then. A pilot performance by high school students for elementary classes Prince Edward County can be seen at: http://youtu.be/WsaHth8bm0s

After families, teachers, children and health care professionals requested the play in storybook form, JC wrote Jake’s full story, published in 2011. The book is available from JC at www.jcsulzenko.com. (ISBN:978-1-926962-08-5)

With its focus on Alzheimer’s disease and complemented by the companion Discussion Guide for teachers, students and community groups, What my grandma means to say gives elementary school-aged children the chance to learn about Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and what they can do to support someone living with the disease.

JC’s award-winning poetry appears in print and online either under her name or as A. Garnett Weiss. She has published three poetry collections: South Shore Suite…Poems (Point Petre Publishing, 2017), Bricolage, A Gathering of Centos (Aeolus House, 2021), and Life, after life—from epitaph to epilogue (Aeolus House 2024 ) Newspapers across the country have carried her prose articles. Her books for children include Boot Crazy and Fat poems Tall poems Long poems Small.

To arrange for a dramatized reading by JC or for more information about JC’s poetry workshops and writing residencies see www.jcsulzenko.com of email infosulzenko@gmail.com.